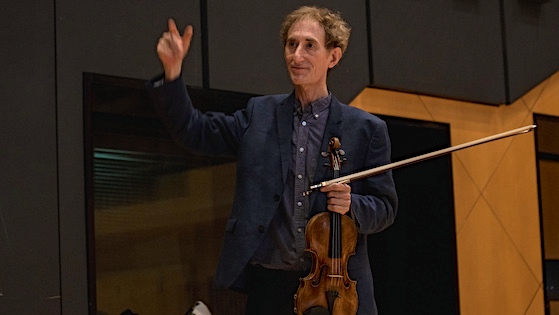

Violinist Simon Fischer Shares Five Things You Can Do Today to Improve Your Rhythm

Violinist and educator Simon Fischer shares his tips and insights for improving one's sense of rhythm

Which would you say is the most important of the two–intonation or rhythm? Most would agree its the latter because rhythm is the backbone of music making. Even Beethoven himself would get frustrated at his students for playing rhythms inaccurately because he felt that meant they lacked focus, discipline and practice. How then can we improve our rhythm?

Guildhall School of Music and Royal Conservatoire of Scotland teaching faculty member violinist Simon Fischer shares his expert advice on the topic.

Violinist Simon Fischer Lets Us in on Five Crucial Tips Things to Improve Our Rhythm

Playing well but without rhythm

The three chief elements of playing music on any instrument are pitch, sound and rhythm. In contrast to the keyboard, where all the notes are ready, a particular problem exists on string instruments because of the initial challenge of playing a note in tune and with a good sound. As a result, many students (at every level) easily fall into the trap of ending up trying to make a performance out of playing only ‘'good-sounding, in-tune notes.’'

Yet, musical rhythm is the single-most important element of the three. Every note must be in tune, and every note must be pure; but in the end, it is through rhythm that musical expression is created and communicated.

Feeling the underlying pulse

It is one thing to play the written note-values. It is another thing altogether to play those rhythms while feeling an underlying pulse. You need to have the ‘'tum ta-ta, tum ta-ta’', or '‘dum, dum, dum, dum’' in the background. This underlying pulse is the ground that the printed rhythms stand on.

Again, it is because of the complexity of playing a note in tune, and with the right sound, that the background pulse may be forgotten.

Apart from robbing the music of rhythmic expression, a lack of underlying pulse may often make the playing appear too mentally-controlled, and therefore detached. When the written note-values sit on top of a pulse, the playing gains a different quality of natural flow and communication.

Sub-dividing

Part of feeling the underlying pulse lies in sub-dividing all longer notes into smaller units. When playing quarters, you need to feel eighths; when playing, say, a dotted eighth followed by a sixteenth, you need to feel four sixteenths.

Understanding technical and musical timing

There is often a difference between the exact moment when a note should actually sound, and the technical preparation for it. In smooth string-crossing, the bow must begin to move towards the new string before that string is sounded; fingers often need to be prepared on the string ahead of the bow; shifts must begin before the moment that you want the finger to arrive; and so on. All these cause rhythmic uncertainty. Such problems are cured automatically through good listening, but technical understanding is always a great help.

Sound + silence = note value

When a note should not sound for as long as its printed value – for example, separated strokes in baroque or classical music, or if a note-head has a dot over it – time must not be stolen from the space before the next note.

If, say, a quarter with a dot overhead is played as a dotted-eighth, the silence after it must equal a sixteenth. Clipping the beat, by cutting the value of the silence, causes hurrying and lack of rhythmic control. The simple formula of sound + silence = note value must always be at the front of the mind.

The overall cure for such problems lies in sub-dividing and close listening.

–Simon

Do you have an idea for a blog or news tip? Simply email: [email protected]

Simon Fischer is recognised as one of the pre-eminent musicians of our time, enjoying a distinguished and wide-ranging career as a performer, educator and recording artist. As a recitalist he has performed in the UK, the USA, Europe and Australia, at venues including the Wigmore Hall and the Purcell Room. Alongside standard repertoire he delights audiences by performing his own transcriptions of famous works by composers such as Tchaikovsky, Mendelssohn, Johann Strauss, Rossini and Purcell. For many years Simon played duo recitals with his father, the pianist Raymond Fischer. Amongst UK and foreign touring projects they played the three Brahms Sonatas in a live broadcast from Sydney, Australia. These Sonatas have also been recorded on CD, receiving high praise in Gramophone Magazine.

april 2024

may 2024

![VC VOX POP | “Which Musicians From The Past Do You Take Your Greatest Inspiration From?” [Q&A] - image attachment](https://www.theviolinchannel.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/bronislaw-huberman-violinist-cover-800x600.jpg)

![The Winners and Grinners – 2017 International Prize Winners [CONGRATS] - image attachment](https://www.theviolinchannel.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/ARD-International-Violin-Competition-Prize-Winners-Cover-800x600.jpg)