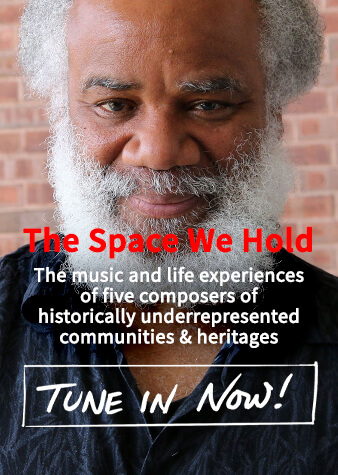

Nora Holt — Composer, Singer, and Music Critic

Holt lived from 1885 – 1974 and was a key figure in both the Chicago Black Renaissance and the Harlem Renaissance

A series of firsts

In June 1918, the Chicago Defender – an early Black periodical– noted that Nora Holt (1884/5-1974) had become the first African-American to graduate with a Master’s degree in music. Mrs. Holt, the paper noted, “won her degree and highest honors by presenting a symphonic rhapsody of forty-two pages for an hundred-piece symphony orchestra, and incidentally has the honor of being the only artist of the Race holding the degree of M.M.”

While Holt was a prolific composer in her early years, this was but one of the contributions that Holt made to the musical world. She spent many years working as a music critic, and in this capacity, she became one of the first Black women whose writing on music broke into the public sphere of print. In addition, she founded the National Association of Negro Musicians, which continues to carry out crucial work in advancing the cause of Black classical musicians. Holt also had a parallel career as a singer, gained notoriety as a socialite, and was a key figure in both the Chicago Black Renaissance and the Harlem Renaissance. Why is it, then, that she is not yet a household name?

The Chicago Defender

As a composer, Holt wrote over 200 works, but the vast majority were lost forever after the scores were stolen from storage while she was away on a singing tour of Europe and Asia. Following this tragic theft, Holt refused to return to composing, and only two of her works survive.

One of Holt’s most significant roles was her work as a music critic for the Chicago Defender, a prominent Black periodical. Founded in 1905, the Defender played a pivotal role in the Great Migration, drawing many African-Americans to northern urban centers and giving them a print platform once they had arrived. By the 1920s, the paper had established itself as the nation’s leading Black periodical: it had a readership exceeding 150,000, and many of its readers resided outside of Chicago.

It was not merely Holt’s presence at the paper that was revolutionary, however. Harvard historian Dr. Lucy Caplan contends that Holt’s criticism was directly informed by her lived experiences as a Black woman and that her work, therefore, expanded both the scope and the methods of music criticism. Holt’s work was deeply focused on collaboration and prioritized modes of knowledge production that favored multiple perspectives over the individualism that dominated Western thinking.

Having carved out a space for Black women to publish work on classical music, Holt was also able to pass on the torch at the conclusion of her tenure by handing down her role as the Defender’s music critic to Maude Roberts George.

Holt was to return to music criticism in 1953 when she became the host of a new radio show on New York’s WLIB network entitled “Nora Holt’s Concert Showcase.” The program was broadcast weekly from Harlem, and featured mostly Black performers and composers.

Holt and the Black community

Dr. Samantha Ege, a musicologist at Oxford University, notes that Holt did a great deal of work in laying the foundations for other prominent Black women in classical music such as Florence Price, Estella Conway Bonds, and Maude Roberts George. The public and historiographical nature of the published word was crucial to Holt’s work: in her role at the Defender, she was able to document the work of many Black musicians whose work would otherwise have had no historical record.

Caplan notes that in Holt’s time, many Black musicians were operating via what Naomi André calls a “shadow culture”: Black musical activity ran parallel to mainstream musical culture, but remained largely unacknowledged and unsupported. By bringing Black musical culture to the print domain, Holt was able to cast a spotlight on cultural activity that had previously been happening in the shadows.

A further contribution to the wider community of Black musical culture came when Holt founded the National Association of Negro Musicians (NANM) in 1919, alongside colleague Henry Lee Grant. The organization’s main mission was to promote, preserve, and support music created and performed by African Americans, and its work continues into the present day. Over the course of its history, NAMN has provided scholarships to many prominent Black composers, such as Florence Price. The association has also established a library, which ensures that there is one centralized location where African-American music can be stored or put forward for publication.

Holt as a scandalous socialite

By the time of her graduation from the Chicago Musical College, Holt had been married three (or possibly four) times. Her third husband, the businessman George Holt, died in 1921, leaving his widow a generous inheritance.

The messy conclusion of Holt’s next marriage (to Joseph Ray, who worked for a prominent steel magnate) was also a rather lucrative affair, but the details of it were so gossip-inducing that Holt was forced to abandon Chicago for New York. Here she became associated with some of the most prominent voices of the Harlem Renaissance, such as the writer Langston Hughes, and positioned herself at the center of its culture.

Holt’s reputation was such that the writer Carl van Vechten fictionalized her in a controversial 1926 novel, taking some of Holt’s more extravagant personality traits and transforming them into the character of Lasca Sartoris. Sartoris, who New Yorker critic Kelefa Sanneh describes as a “debauched socialite”, is portrayed as a wealthy, glamourous femme fatale.

Not everyone was impressed with Holt’s colorful personal life, however, and her critics often used her lifestyle as an excuse to dismiss her as indecorous. As it turns out, it was precisely this aspect of Holt’s personality that pushed the boundaries of the way that Black musicians were able to present themselves. As Caplan argues, the “scantily clad Parisian nightclub chanteuse could also be the writer exhorting readers to listen to symphonies.” Holt, therefore, resisted the usual pressure for Black classical musicians to have to present as respectable, so that they would be seen as “rising above” the perceived natural inferiority of their race.

Music

One of Holt’s only surviving works is this short piano piece, Negro Dance, which dates from 1921. According to Ege, the piece draws inspiration from African-American antebellum rural dance music, most notably the Pattin’ Juba. This musical pattern derives from a plantation dance that was originally brought to Charleston by slaves and uses only the body – slapping and patting of the arms, legs, chest, and cheeks, alongside stomping with the feet – to create rhythm.

The Pattin’ Juba uses only the body out of necessity. In the wake of the Stono Rebellion, which took place in South Carolina in 1739, plantation owners forbade their slaves from playing any rhythmic instruments for fear that they were hiding coded messages in their drumming patterns, and so the body became the primary carrier of rhythm. Florence Price later used the Pattin’ Juba in the third movement of her Symphony No. 1.

You can hear Dr. Samantha Ege performing Holt’s Negro Dance (1929) below:

april 2024

may 2024